Curated by Maurizio Bortolotti

12 November 2021-2 April 2022

THE IDENTITY OF MONGOLIAN ART IN THE HEART OF EURASIA.

It is difficult to understand art in Asia without taking into account its complexity. While globalization has provided an important opportunity in recent decades, enabling it to develop economically and in some cases to overcome the West, it has also confirmed its cultural reception, concealing the most dynamic parts that are local identities. Asia is made up of a myriad of different realities that make the continent a fertile ground for economic and cultural events that are changing the course of the 21st century.

Within this mosaic of identities, Mongolia deserves a place of its own. The country is located on a single large plateau, bordering Russia and China, with a population of about 3 million inhabitants, 800,000 of whom still live as nomads. After gaining independence in 1992, the country is the only democracy in the area still seeking its own identity as a modern country.

The recent constitution of Mongolia has in fact produced a climate of change that has stimulated artistic production. After the end of the Soviet influence with social realism, the Mongol artists directed their production towards two poles: the international art movements of Global Conceptualism, which appears as a form of legitimate updating, and the tradition of Thangka painting, combined with the celebration of the myth of Genghis Khan and the nomadism that still today, centuries later, influence the daily life of Mongolia.

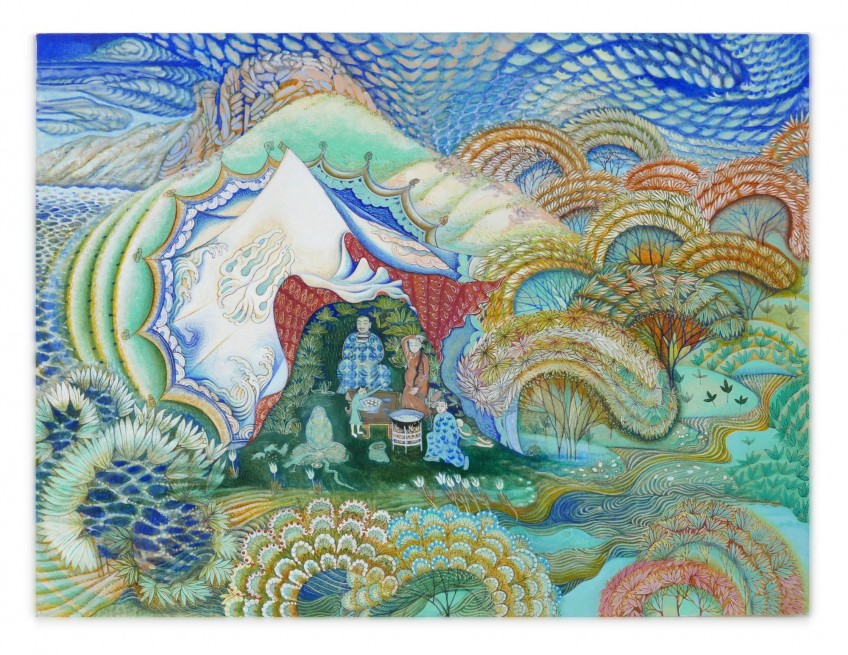

From a more general point of view, we can say that in Asian art the Western concept of “new” has never been assimilated. Even when Western artistic modes spread through globalization, art in Asia remained anchored in a constant dialogue with local tradition. For the same reason, one of the most lively artistic currents in contemporary Mongolia is the one that today re-presents the tradition of Thangka Buddhist painting, declining it in an infinite variety of ways.

The modes of actualization of this tradition pass through contamination with other visual-narrative genres, such as that of the Manga cartoons or the insertion of episodes related to everyday life, to build a new type of narration, who wants to represent the present time.

Originally, it was a kind of religious painting related to the description of Buddha’s prerogatives. Although the approach to this genre is free and not subject to rigid stylistic canons, Thangka painting follows decorative schemes codified with compositions of figures suspended in a perspective space.

In the paintings of the younger generation, the motifs or figures rather than having the meanings proper to the tradition, refer to social and political facts of contemporary Mongolia, developing a self-narration of the current destiny of the country. Figures of horses, knights or Buddha are mixed with contingent facts, which belong to the life of the present. In a vision of reality in which even earth and heaven are spiritual entities that are set against the background of the daily life of a people whose roots are nomadic culture.

Nomadism is present in the stories and in the social and family imagination, handed down also by those who have urbanized in the capital Ulaanbaatar for over two generations. The search for a contemporary identity by a country where nature maintains the strength of its origins, dating back millions of years ago, and part of the population still lives in the nomadic state, with precise rules of life, clashes with the urbanization of the Mongols in the capital Ulaanbaatar, where you live a modern life.

The great narration of the nomadic condition is in fact the nourishment of the Mongolian art, since this narration acts as soundtrack also to the urban life of the great city; on the outskirts of which, and in the vast territory of the country, Nomads still stay in typical Ger tents and ride horses. The tension that arises from Mongolian art is born precisely from the contrast that the Mongols live between modern life and their imagination, populated by the memory of nomadic life. It is a state of mind, but also an identity condition, in which there is an obvious attempt to connect traditional roots with contemporary life. And although there is a widespread knowledge of international art, the Mongolian art scene is mainly focused on itself, in search of its own position that distinguishes it from the rest of Asian art.

Paradoxically, the great theme of Mongolian art is the representation of the myth of nomadic life at a time when the tendency to abandon it in favour of urban life is becoming increasingly evident. It is the reservoir of inspiration of many artists, closely connected with the phase of political and social transformation that the country is experiencing.

For this exhibition we have selected some artists who are representative of the artistic scene in Mongolia, of which we present for the first time in Italy a review.

The issue of urbanization, the transition from nomadic life to the urban condition is the background to the social narrative of the photographer Esunge, who portrays the nomads who have recently settled in the suburbs of the capital Ulaanbaatar. Their lives in the traditional Ger, permanently installed in the suburbs of the city, near the houses, are told without embellishments, trying to grasp the traits of a once proud existence, which represented the national pride. The realism of the images deeply digs the myth of nomadism, even in the condition of survival of the dusty suburbs of the city. The series of portraits is an attempt to fix in the eyes and bodies, old and young, the otherness of the nomadic condition. The portrait of a young man, whose regular features recall a warrior of other times, in his red blouse of traditional workmanship is distinguished from the others because he appears to us as the hero protagonist of an epic narrative of the nation. The attention to the suburbs of the capital, which recall the many shanty town scattered around the world, contrasts with the faces of the nomads, whose intense looks seem to keep the vision of the boundless prairies even in the condition of segregation of the suburbs. It is the tragedy of the process of change in the country in progress, in which the protagonists themselves participate in amazement. The changes affect this exemplary humanity that has abandoned a condition of secular life because of the uncertainty of a future that appears inevitable. In the images of Esunge there is concentrated the search for identity of a people, which is gradually abandoning the traditional costumes while continuing to wear them with pride. Family life in the Ger is timeless, but outside the context of the suburbs describes the urgency of a radical transformation of the country. Modernity dazzles and attracts nomads like moths to the light of a future that seems to offer them no space other than miserable life and without conditions of the outskirts.

Contrary to Esunge’s realism, the imaginary of nomadic life is well represented in the work of Dolgor Serod, who was a pupil of one of the leading masters of Thangka painting in Mongolia. In her work, the decorative and narrative components find a harmonious balance in the name of the Buddhist painting tradition. The scenes of traditional nomadic life are adapted to the decorative structure of the paintings, with flows of figures that move in accordance with secular compositional schemes. In the painting “Mongolian Life” there is the evocation of a glorious past, in which all the ideal elements of nomadic life are orchestrated: the structure of the gear with its internal organization, the altar dedicated to the ancestors opposite of the entrance, to the left the male area, to the right the area of women and children. The herds and horses, traditional means of transport, complete a mythical Eden in the imagination of the Mongols, dreamed even today despite the city life made chaotic by traffic, where the inhabitants live in modern buildings such as those found in residential areas of Chinese cities. The series “Cherry Blossom” is the tale of an ideal nomadic life lost forever. The erotic scenes blend with the resumption of nature and men are in perfect harmony with natural life. While the series dedicated to markets, with the combination of gear to buildings or the representation of the old black market (“Old Back Market”) more closely reflect the reality of contemporary Mongolia. The structures of the paintings in this series follow an archaic scheme of presentation, but the swarm of everyday life, which is the real protagonist of the images, tells of a lifestyle and a sociality with an open structure, organized according to a horizontal scheme instead of pyramidal and hierarchical, which is typical of sedentary civilizations.

For Nomin Bold the traditional representation is the background to insertions of figures that recall the feminine identity. In her compositions, which refer to Thangka painting, female images or those of the Buddha alternate with skulls and other figures wearing gas masks. In her works there is a reinvention of iconography and traditional space. It is a modern space where decorative patterns create a three-dimensional representation. The classical representation, while being the basis and support to the narrative, is continually broken and renewed. Compared to traditional iconography, the artist completely rethinks the decorative structure on which the narrative rests, creating rigorous grids on which are grafted the compositions made with myriad of figures that refer to modern life. There is a double research that completely modernizes the Thangka representation, both in the reinvention of the space of the representation and in the choice of the subjects. In her works the two researches appear complementary but well distinct. In a recent installation, gas masks are crocheted with colored wool and hung on a horizontal wooden bar suspended from the ground, or resting on vertical metal rods. It is a strong stand against pollution and environmental sustainability issues. Despite the apparent fidelity to tradition, the works of Nomin Bold are highly innovative in terms of both iconography and composition, as well as the modernity of the issues addressed. The frontal presentation of the images contrasts with the complexity of the narrative, in which the decorative structure becomes the support for an epic narrative to the feminine.

Even in Baatarzorig Batjargal’s work, tradition is reinterpreted, but the composition with decorative patterns in favor of a broad epic narrative, in which appear battles of the past in which ancient knights participate, in a tangle of half-human and half-animal figures. Its warriors, human beings with animal heads, or giant snakes with dragon faces, give the complex narrative of Baatarzorig Batjargal (curiously, the prefix “Baatar” of its name means hero) the traits of the mythological Monarchy. The Thangka iconography is developed here with symbolic representations of animals and mythological creatures present in Buddhist decorations and ceremonies. The great epic narrative is the central theme of his work, but even in his paintings the reinterpretation of traditional iconography is punctuated by the insertion of elements that populate the imagination of modern Mongolia. In addition to the facts of current politics, he includes quotations that refer to the times of the influence of the Soviet Union. The fantastic traditional repertoire is enriched by the inclusion of bold pop images, such as the series of paintings and sculptures of the Buddha with the head of Mickey Mouse. This quote is not a superficial reference to Western modern art. It shows us the contamination of traditional culture, and it is once again the demonstration of how much the clash between modern life and that of the past is the center through which the search for a cultural and social identity of Mongolia develops. The fantastic figures of the paintings and the references to the profane iconography of modernity tell how the clash between the demons of the past and those of the present did not subside in the vision of the artist, who, although apparently far, it deeply captures the turmoil of today’s Mongolia.

Finally, in the work of Munkhjargal Munkhuu, the youngest of the artists invited, there is the coolest attempt among those proposed to renew Thangka painting combining it with an iconography that recalls the imaginary Manga. In this contamination between the two genres, actuality themes are touched by mixing them with figures of the Buddhist tradition, which only marginally appear in the complex compositions. In his paintings the crowding is greater than in tradition and the three-dimensional space is fluid, solely determined by the movement and the interweaving of the figures. The iconography and type of narration are completely renewed. There are only vague references to the images of the past, the whole representation is projected into the actuality. The works are full of references to events that have influenced social life, with portraits of politicians and leaders of public life in the country, alternating with images of cartoon characters armed, or icons of modernity such as the Rubik’s Cube, KFC fried chicken bags, signs of Mongolian Americanization. In his compositions often stand out numbers that have a symbolic and magical value that are intertwined with the direct coverage of the country. The composition in the paintings is decidedly modern and break with traditional patterns, while maintaining a general layout that recalls the traditional but making it more crowded with characters and objects, almost asphyxiated. There is a dynamism and vitality that tell the frenzy of modern life in the country. His paintings are great allegorical narratives of Mongol society and a pitiless mirror of life in the modern city. The artist’s attitude is critical of a society that, seen with his eyes, appears chaotic and in search of a difficult balance for the identity of an ancient country, but still extraordinarily at the dawn of a new era.